Research Projects

Current Research

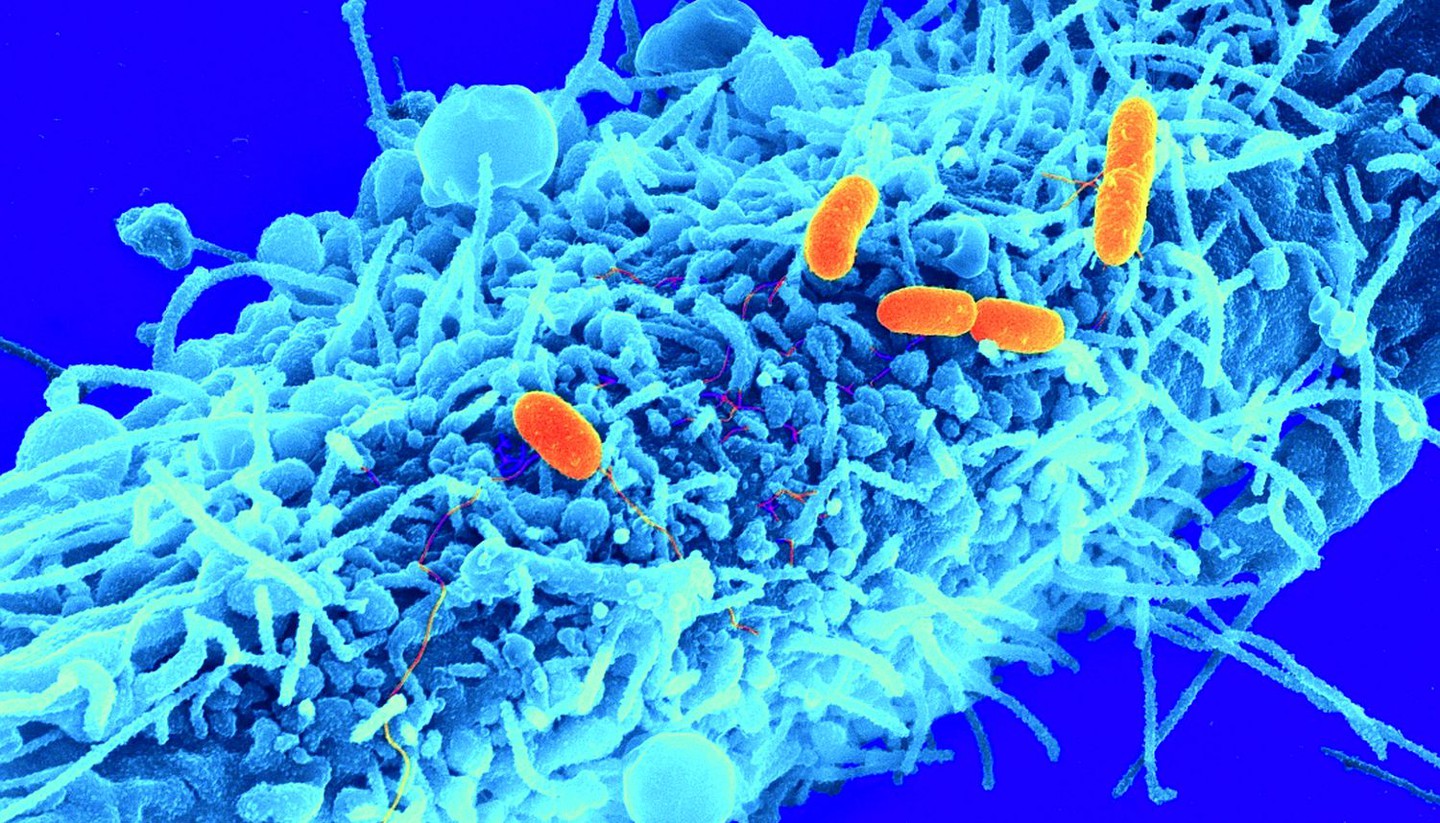

Bacterial Disease and Host-Pathogen Interactions

Manipulation of human host cells is a fundamental challenge for all pathogens. To understand host-pathogen interaction and pathogenesis, we examine the characteristics, functionalities and interactions of molecular structures involved in the survival and multiplication of bacteria within the host. One example of such nanomachine is the type III secretion system (T3SS), a membrane-embedded nanosyringe-like complex that allows the direct delivery of proteins, known as effectors, into the cytosol of human cells. The T3SS is a highly conserved virulence machinery of Gram-negative bacteria, and thus it represents an attractive target for novel anti-infectives. The structural core of the T3SS is a ~3.5 multi-megadalton complex assembled from more than fifteen different proteins that spans the two lipid bilayers of Gram-negative bacteria. The current challenge we face is to understand how structural switches in this bacterial secretion apparatus allow the recognition and secretion of effectors in a hierarchical manner and what kind of protein-protein interactions can drive bacterial invasion. We integrate high-end technologies like X-ray lasers and electron cryo-microscopes with other biophysical methodologies to study the functional dependence of structural determinants in T3SSs from water-borne bacterial pathogens and investigate the rules for effector protein secretion, transport dynamics and regulation of the T3SS.

In addition, we have a strong interest in uncovering the strategies used by Gram-negative organisms to subvert the antibacterial response of human cells. Components of the tip of the T3SS apparatus interact with host membranes to allow the translocation of effectors directly to the human cell cytosol. How the translocon components assemble and insert into host membranes to form pores are under investigation. We also focus on the molecular interactions of T3SS effector proteins with host components and their signaling cascade that drives cellular subversion. Shigella, the causative agent of diarrhoea and other gut-associated diseases, invades the human colonic epithelium and avoids clearance by promoting cell death of resident immune cells in the gut. Different modalities of cell death (pyroptosis, necroptosis and cell death programs involving alternative caspases) have been linked to the killing mechanism. Although these modalities may not be mutually exclusive and may progress simultaneously, we evaluate the contribution of each program in dying cells with special focus on the T3SS dependency.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an adaptive environmental bacterium and an important opportunistic pathogen, which causes devastating acute as well as chronic, persistent infections. Due to its high ability of adaptation to different adverse environmental settings and multidrug resistance, this opportunistic pathogen poses a particular threat in public health and thus the urgency of developing new antibiotics is critical. To bypass drug resistance, we are interested in finding novel molecular mechanisms underlying virulence in P. aeruginosa. For this, we combine multiple omics data of clinical isolates with microbiological, biophysical and structural biology methodologies to elucidate structure-function relationships of novel proteins associated with virulence in P. aeruginosa.

We integrate interdisciplinary approaches to advance our understanding of the assembly and three dimensional structure of key bacterial components involved in virulence pathways and their interaction with the host responses to allow us the design of molecular drugs for the treatment of Gram-negative bacterial infections.

Future projects and goals

Our underlying biological goal is to understand in-depth the process by which Type 3 Secretion Systems orchestrate the sequential order of effector translocation and trigger controlled subversion of a target cell. In addition, we aim to identify novel bacterial protein complexes essential for P. aeruginosa infections. For this, we will combine high precision imaging technologies with microbiological and biophysical methodologies to examine the dynamic process of a bacterial infection at sub-nanoscale resolution.